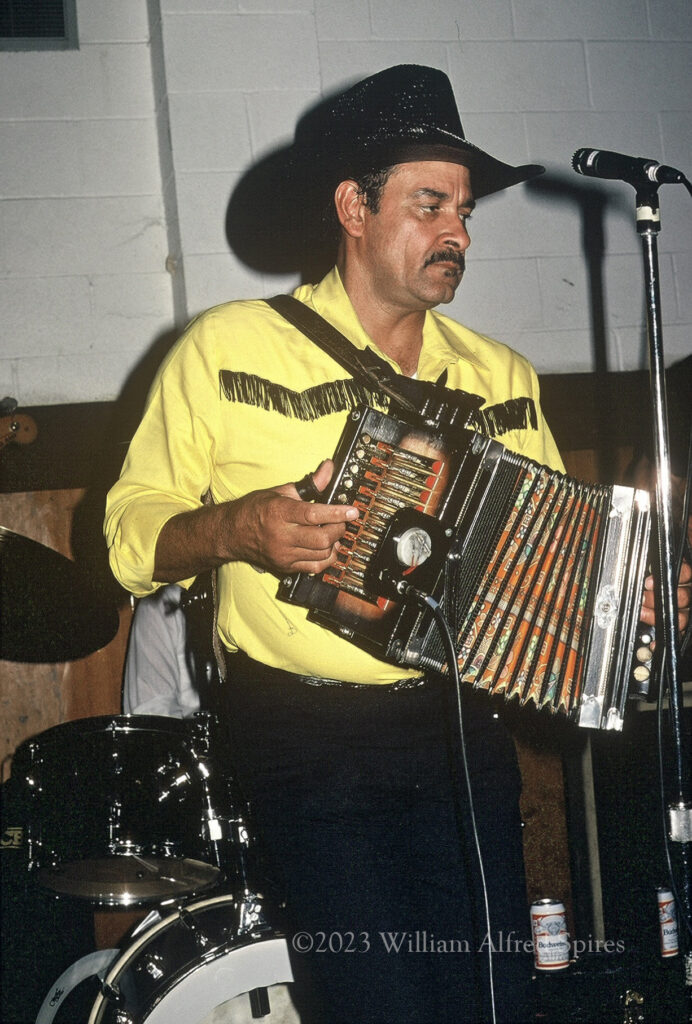

THE MUSIC OF DANNY POULLARD

This paper will focus on the life and music of Danny Poullard, accordionist and singer, one of the traditional performers who brought Cajun and Creole music to the west coast after World War II. I have performed with Danny as a fiddler since 1976. After the death of Lawtell accordionist John Semien in 1984, Danny Poullard is the most influential figure in this tradition west of Texas. (California Folklore Society members may remember his playing from our plenary session in 1984.)

Active tradition bearers carried these traditions here during the 2nd World War migrations and during the post-War diaspora. These musicians passed along repertoire, performance style, and beliefs about music encouraging one another and sharing professional opportunities.

These communities were highlighted by Chris Strachwitz. Passionate in his quest to find and preserve vernacular music, Chris Strachwitz sought the western echo of this music in Northern California. With his keen and unfailing instincts, Strachwitz found it on Saturday nights at the Roman Catholic parish halls of St. Francis of Assissi (East Palo Alto), St. Mark’s (Richmond), and St. Paul of the Shipwreck (Hunter’s Point), parishes are home to migrants from Louisiana and East Texas. The music on these occasions is provided by the-typical ensemble of single-row diatonic accordion, fiddle, guitar, and percussion, with singing in French. The Poullard traditions took root here and flourished. With Strachwitz’ efforts and those of film make Les Blank, the Creole community came to widespread attention in Northern California.

Danny Poullard’s family background in traditional Creole music can be traced through four generations. His great-grandfather Alphonse Poullard (born c. 1860) was a fiddler. So also was Danny’s grandfather Theophile Poullard. Theophile was a friend of the great Amedee Ardoin, who recorded a tune named after Theophile’s brother Alcee (“La Valse de Alcee Poullard” with Dennis McGee, violin. Recorded November 21, 1930 in New Orleans. Brunswick #495). Danny also recalls accordionists in his grandparent’s generation on his mother’s side. Edna Daigle’s (Danny’s grandmother) brother UIysses is known to have played and to have instructed Danny’s father, John.

Both grandfather Theophile and great uncle Ulysses were born between the small towns of Iota and Mowata. UIlysses. Born before 1900, they must have been in the vanguard of Creole accordion players. Both Amede Ardoin and Dennis McGee knew Theophile. Danny to this day remembers Theophile’s playing as closer in style to Dennis McGee’s than to Canray Fontenot’s, for example. No recordings are known to exist of Theophile, much less of his father.

John Poullard was born near Iota in 1910. Under the influence of his uncle Ulysses, of his father, and of his grandfather, John began playing in his early teens. John married Dorcena Daigle in 1930 and began sharecropping southeast of Eunice, near Ritchie. Before and just after his marriage John played with the well-known accordionist and builder Sidney Brown from Lawtell. Danny recalls that both would play together after work and on weekends, using the same accordion. In the late 1930s, after John had learned to play, he performed near Eunice and Basile, when the chief musical function was still the bal de maison or “house dance.”

The bal de maison flourished before the advent of bars, night clubs, and road houses. The format was essentially the same among Black and Anglo-French households. Admittance was invitational by word of mouth; unmarried young women were chaperoned. Often the host’s influence would extend to the point of choosing which single men would be admitted to the crowded dance floor. Liquor was strongly prohibited: drinkers either drank in town before the dance or hid flasks of “white mule” in the yard or under the house. A man stepping out for a libation might excuse himself by saying, “I’ve got to check my traps.”

Although the host of a bal de maison would direct the proceedings with an eye to the prevention of ill-feelings and violence, blood could flow. Around 1937, after playing for a dance near Eunice, John Poullard was shot through the chest by an unknown gunman. The story at the time was that he had been confused with another person and shot by a white assailant. Danny’s belief is that the gunman may have been black and that musical rivalries may have been involved. (White singer Meus Lafleur was killed in Basile in 1928 in a similar atmosphere, and stories are not yet at rest about the rivalries between Amedee Ardoin and the black fiddler Douglas Bellard.) Whatever the circumstances that led to the shooting, John Poullard lay near death for some months with a large exit wound on the front of his chest near his heart. He survived, but the event marked the end of his musical career except when he sat in as a guest with other groups.

John Poullard lives today (1985) in Beaumont Texas. He has renewed his accordion playing in the last two decades. It is unfortunate that his career suffered so long an interruption, but this background outline shows that John’s son Danny Poullard is heir to a rich musical legacy indeed.

Danny Poullard was born on January 10, 1938, one of eleven children. Because his father had abandoned the musician’s life before Danny was born, Danny’s first musical impressions were of his grandfather Theophile’s fiddling. Theophile, in his early seventies, was semi-retired, living outside of Eunice beyond the range of electrical hookups. Danny spent considerable time with his grandparents during his early years. When playing, Theophile remembered Amedee Ardoin and Dennis McGee with respect and affection. Danny formed a lasting impression of old-time folklife from this association. He remembers many of Theophile’s tunes to this day, among them “Bayou Pom Pom,” “La Valse A Point Noir,” “I Want To Get Married ‘cause The Chicken Won’t Lay.”and an intricate one-step that Lawrence Walker recorded as the “Wandering Aces Special.”

Other relatives played an important part in Danny’s early listening years. Danny remembers one of John’s brothers, Henry, [1928–1982]. as being equally talented at both traditional Creole and newer Zydeco styles. Henry Poullard performed at least through the 1950’s.

Musicians outside Danny’s family also provided much influence. Among these may be mentioned the well-known Doland “Eraste” Carriere. “Red” Semien, from Lawtell, also played accordion at church and house dances. “Red “was the oldest of the Semien brothers, many of whom later moved to the west coast. In Lake Charles, Danny heard Raymond La Tour, brother of Zydeco accordionist Wilfred LaTour, now active in Watts, California (Danny claims to have heard principally Cajun and Zydeco music all through his childhood until moving to Texas in 1951.)

Danny also remembers the dance hall of Fremont Fontenot, twelve miles south of Eunice near Basile, as a special musical center. Fremont Fontenot was host to the foremost Creole musicians of the 1940s and 1950s. At the dance hall that Fremont himself had built, Danny heard for the first time accordionist Alphonse “Bois Sec” Ardoin Amede Ardoin’s nephew. and fiddler Canray Fontenot These well-known traditional players alternated weekends with emerging Zydeco stars Clifton and Cleveland Chenier. The Poullard family attended both types of events, traveling to Basile by wagon or car.

Danny formed his first memories of his father’s playing It was also at Fontenot’s dance hall. Although John had stopped appearing professionally after the shooting, he would frequently sit in for Alphonse “Bois Sec” Ardoin at these dances in Basile. Fremont Fontenot assisted likewise. Danny remembers these occasions with warmth, even though violence marred many of them. At 85 years, (1985) Fremont Fontenot has been given much recognition as a musician. He is certainly due equal credit for his efforts as an impresario who made a great contribution by nurturing Cajun and Zydeco music at a crucial period of change and expansion.

The influences which Danny had been exposed to since birth surfaced in his own ambition at the age of ten years. He had a great desire for an accordion at this time and says that he could have afforded one from his own savings. Repeated requests, however, met with denial from his father. Two reasons seem to contribute to this. Certainly, John’s near-fatal gunshot wound left him with anxious memories of musical life and its attendant rivalries. Violence was commonplace at dances. It could also be that the social position of a-musician was dropping at this time. In any case, Danny deferred to his father’s wishes and dropped his requests to own and play an accordion. Today he feels that his father knows this early restriction was overly harsh. When Danny finally took up the accordion his father was, in fact, quite pleased.

Danny went through grammar school at St. Matilda’s, a parochial school in Eunice, de facto segregated. Dances were then—and are—a frequent social focus at the parish hall. Danny learned English here, having spoken French with his family before school.

In 1951 John Poullard took the profits saved from years of sharecropping and moved the family to Beaumont, Texas. They left behind Fremont Fontenot’s dance hall, the sharecropping fields of St. Landry Parish, and the many generations of Poullards who rest in the cemetery of St. Matilda’s.

The relocation of the Poullards came at a time of considerable migration from Louisiana. Danny recalls that when the demand for workers was satisfied in Lake Charles, movement progressed to Port Arthur, Texas, then to Beaumont and Wiedlands. John Poullard found work in an iron foundry. After being laid off, he went to work for the County, driving heavy equipment and landscaping. He continued in that position until his retirement.

Danny does not recall an intense musical scene in Beaumont, remembering only that an accordionist named Napoleon Phillory played and sang in French, in a suburb of Beaumont called Cheats. Phillory’s wife played drums. Aside from this, Danny’s contact with French music was limited to Saturday night radio broadcasts from Port Arthur. The scarcity of older music in Texas at this time is not surprising: whatever French music was to be found at this time was more likely the Zydeco style emerging around Houston.

Danny went to high school in Beaumont, joined the Army in 1956, served in Germany, and mustered out in 1958. He remained in Beaumont until moving to San Francisco in 1961; there, he married, became a meat cutter, and made his home in Hunter’s Point.

Danny is hard pressed to say just when he drifted into music. He says that he “always” had a guitar around and he used to play it after the fashion of fiddler Canray Fontenot, that is, using extended left hand slides to find melodies. He purchased an organ for his daughter Michele, and began to learn Cajun melodies on the keyboard. Around 1962 he bought a harmonica and began to learn the push pull system which is common to both the harmonica and the Cajun accordion. By this time he had found many friends and relatives living on the west coast, especially in the Bay Area.

Danny was invited at this time to a house dance at the home of accordionist Louis Bourdelon, where he heard live Cajun music for the first time since leaving Beaumont. Here Abraham Guillory, a fiddler, accordionist, and harmonica player from Iota was playing dance music with two of his brothers. All formed a musical circle around John Semien, considered to have been the most influential Cajun musician in California at that time.

John Semien was born in Lawtell, Louisiana in 1919. He was the son of Louis Semien [1889–1975] and Alice Carriere [born c. 1900]. Both of his parents were accordionists and his mother Alice was the first cousin of Eraste and Joseph Carriere. Semien moved to the west coast in 1943, after serving in the army. He is remembered as having played for dancers in the Fillmore district of San Francisco from the time of his arrival. He was probably the founder of California’s first Cajun band, the Opelousas Playboys. (The name came from Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys.) There were for John Semien and his public three important musical settings at this time: the bal de maison or house dance, the church hall dance, and the private club.

The bal de maison was a direct counterpart of its Louisiana prototype. Migrants assembled to enjoy music and dance. The occasion of such a bal might have been a confirmation party, the departure or return of a member of the armed forces, or the arrival of visitors or migrants from Louisiana or Texas. Semien played for countless such occasions.

The church hall dance was a regular feature of Roman Catholic churches with congregations from Louisiana. A fixed door charge; proceeds from food and drinks and special raffles and sales allowed the band to be paid with other profits being earmarked for church programs. Semien, the Guillory brothers, and other musicians made up the nucleus of this important scene.

Private clubs took up the slack between the house dance and church hall dances. The general intent of these clubs was to create an atmosphere where music, dance, social drinking and French language could flourish apart from bars. Music was provided by live musicians whenever possible. Again, John Semien was a key figure. The profit margin from twenty-eight drinks to a fifth of liquor proved ample to sustain these events, held in a remodeled garage or rented storefront. The private club resembles to some extent the Louisiana “camp” or buvette, an outbuilding near a private home where similar proceedings are countenanced. Two of these clubs seem to have been most important: the “Bons Amis Club” and the “Progressive Sportsman’s Club” which is still active at a fixed address in the Fillmore District.

Attracted to this familiar scene, Danny Poullard was befriended by John Semien and by the Guillory brothers. His active interest in music increased rapidly after he went to the dance at Louis Bourdelon’s. He met more friends from Eunice, some of whom he had not seen since childhood. He attended the functions of the Bons Amis Club and began playing triangle and rub-board at these events, as as he had done with his uncle Henry Poullard.

L to R Junior Felton, George Broussard, Ben Guillory, John Semien. Photo courtesy of Chris Simon

As Danny was moving into this scene, Semien formed The Opelousas Playboys. All the members were from Louisiana: fiddler Ben Guillory from Basile [1915–1978] guitarist Junior Felton from Slidell [born 1940] and drummer and singer George Broussard from Tyrone [born 1934]. They began playing frequent dances in this configuration at parish dances. Danny visited Semien often at this time, and attended the dances regularly.

Louis Bourdelon suffered a stroke and passed his accordion along to Semien. Semien had several instruments, and sometimes allowed Danny to play Bourdelon’s, which had been built by John Poullard’s friend Sidney Brown. After progress, Semien gave Danny some rudimentary instruction.

Later on in the 1960’s Danny purchased a small single row diatonic accordion from a dealer on Columbus Street in North Beach. He recalls paying twenty-five dollars for the instrument. He practiced in earnest and his progress was soon noticed by fiddler Ulysses Guilbeau, who suggested that Danny get a full-sized accordion. Danny then bought a full-sized Hohner in C major. He also began collecting Cajun records by Alphonse Ardoion, Aldus Roger, and Nathan Abshire from the legendary Jack ‘s Record Store on Page Street.

Instruction from Semien went slowly, as Semien’s short fingers required a technical system which was neither practical nor necessary for Danny. Around 1965 John Poullard visited his son and provided him with more practical help. From his father Danny learned the system whereby melodies are formed beneath four closely grouped fingers and reinforced with octaves. Encouragement and approval meant a great deal to Danny at this time. The visit was a turning point. He was hard-pressed to remember all his father taught him in so brief a period, but these points were reinforced on later visits.

Danny remembers both encouragement and mild derision from his friends; alike, these responses challenged his efforts. Both Ulysses Guilbeau and Semien’s cousin Mrs. Lawrence Garlow were helpful with praise and expressed confidence. On the other hand, when Danny arrived at Mrs. Garlow’s home with his new Hohner accordion, one of his own cousins said he had wasted his money and would never learn to play. Others said he was too old to learn. Danny told them that they would eat their words, deliberately keeping to himself the fact that he came from a long line of accordionists and fiddlers.

While learning accordion, he brought his guitar playing up to performance standards. This enabled him to accompany Semien at house dances where a full band was impractical. Danny gained much experience and many tunes from this work. Junior Felton, perhaps sensing competition, encouraged Danny to learn bass guitar as well. Danny purchased one, learned to play it in short order, and joined the Opelousas Playboys on that instrument.

For Danny, these years between 1968 and 1973 were crucial for the development of technique and repertoire. Style and taste had been formed in Louisiana thirty years earlier. With the additional recorded examples of Nathan Abshire and Aldus Roger as models Danny synthesized a personal style from these musicians and from his family background. By 1973 Danny was able to play proficiently for a full night of dancing.

At this time Semien made a professional move that caused the restructuring of the Opelousas Playboys and that eventually brought Danny to the accordionist’s position. Semien went home to Louisiana, cut an LP with sidemen from around Ville Platte (“John Semien And His Opelousas Playboys” La Louisianne LLC-509] and returned to present his friends and fans with his accomplishment. The musicians who had been appearing with him as the Opelousas Playboys were less than delighted.

It is unclear from accounts whether Semien fired them or if they quit. In any event, after much professional friction fiddler Ben Guillory nominated Danny to play accordion. Semien was indignant but powerless: Guillory and George Broussard took over booking and other arrangements. Semien was particularly irate when they appeared as the Opelousas Playboys in his absence. During band meetings Danny pointed out that none of the current members were from Opelousas and that Semien wasn’t either. He suggested the name “Louisiana Playboys” which met with easy approval.

Semien ultimately visited Danny at home in an attempt to settle matters. Danny found the question of his own right to play accordion somewhat silly, but let his friend get matters off his chest. He argued that Semien ought to be pleased at his former student’s success. Semien was only partially content with this line of reasoning.

Danny was then and still is the first to acknowledge Semien’s importance in the growth of Louisiana music in the Bay Area, and the end of their meeting was that both remained friends. Danny even continued to play electric bass with Semien’s new band.

Independent recognition for the Louisiana Playboys came quickly. Around 1976 Chris Strachwitz arranged for the band to play on a Thanksgiving broadcast on KPFA. This brought them in turn to the attention of Berkeley filmmaker Les Blank, who set up many of their first appearances outside the Creole community. The Louisiana Playboys became well known in these years, appearing at folk festivals, coffeehouses, and in Blank’s film, Garlic is As Good As Ten Mothers. Danny acknowledges the assistance of Les Blank, Chris Strachwitz, and Gerda Daly of Pacifica Radio KPFA in bringing recognition both to his music and to his community.

Musical achievements solidified even as the band suffered setbacks in the late 1970s. First Ben Guillory, Danny’s chief mentor in the Playboys, died suddenly of bone cancer in 1977. Then in March of 1978 Danny underwent triple bypass surgery for a nearly-fatal heart condition. After his recovery that summer, the band reassembled. I filled in after Ben Guillory’s death. These were fruitful years for the other bands as well. John Semien was active with his brothers in Los Angeles and “Queen Ida” Guillory became prominent with her own well-received take on Zydeco. In Beaumont. Danny’s younger brother Edward mastered both accordion and fiddle, recording with Lawrence Ardoin’s band from Durald, Louisiana after study with his father and with Canray Fontenot. (See afterword.)

After Ben Guillory’s death, Danny was the member of the Louisiana Playboys that most strongly insisted on keeping the repertoire French-based. A degree of stress had been felt in the band. George Broussard’s tastes leaned toward Charley Pride-style country music and Junior Felton played and sang “soul music.” (Felton was especially strong covering Sam Cooke.) Broussard and Felton viewed the Playboy’s performances as a chance to showcase these preferences. Danny felt strongly that the general public wanted expressly to hear the Creole and Cajun music of SW Louisiana.

After Ben Guillory’s death, Danny was the member of the Louisiana Playboys that most strongly insisted on keeping the repertoire French-based. A degree of stress had been felt in the band. George Broussard’s tastes leaned toward Charley Pride-style country music and Junior Felton played and sang “soul music.” (Felton was especially strong covering Sam Cooke.) Broussard and Felton viewed the Playboy’s performances as a chance to showcase these preferences. Danny felt strongly that the general public wanted expressly to hear the Creole and Cajun music of SW Louisiana.

John Semien died of lung cancer in 1984 at the age of 65. He had been working as a custodian for many years and his retirement party was planned for his sixty-fifth birthday. Tests taken just before his birthday showed that he had only weeks to live. Danny relates that the retirement party, held in Semien’s hospital suite, was a melancholy one indeed. John Semien is survived by two brothers, Joseph and Edgar, in Los Angeles: both are musicians.

In January of this year (1987) Danny was hospitalized for a severe myocardial infarction. Today he is resuming his work on a reduced basis. He looks back upon fifteen years of music with satisfaction, both for the fulfillment of his own ambitions and for the recognition that he has brought to his familial and community traditions. Until he is able to return to work (as director of the meat department of the Presidio commissary) he is dividing his time between music, his family, and raising horses..

As a concluding remark, I have noted that there can be some resistance to Black Creole musicians playing the repertoire associated with Cajun players. The point need not detain us, but for what it’s worth, a very well-known Cajun musician—native to Evangeline Parish and a Heritage Fellow—once asked Danny Poullard, fourth-generation musician and vitally important active bearer of Louisiana’s musical tradition, “Why don’t you play your own people’s music?”

Mr. Poullard, direct heir to the traditions of Amede Ardoin, Ulysses Daigle, Fremont Fontenot, Alphonse “Bois Sec” Ardoin, and John Poullard entertained the question with all the respect it deserved.

AFTERWORD

I joined Danny Poullard as one of The Louisiana Playboys as a fiddler and singer. We had smooth nights and rough ones, too. At one point Danny spoke to Chris Strachwitz about making a recording and “Mr. Chris” said, “You’re never going to cut a record with that band. Danny’s professional work then continued with the newly-formed—and very successful and influential—California Cajun Orchestra. Although John Semien’s break with the Opelousas Playboys was marked by conflict, I am unaware of any ill feeling between the Playboys and the California Cajun Orchestra as Danny changed horses. Individual musicians and bands alike go their own ways.

Of the members of the Louisiana Playboys, only Junior Felton is alive today. Danny’s younger brother Edward picked up where Danny left off and lives in Texas today, building accordions and performing as an acknowledged master accordionist and fiddler. You can learn more about him here, here and here. Hail and farewell Danny; your work continues.